Michael Brody, Assitant Head of School

In this week’s Parsha, Ki Tavo, Moses shares many laws and obligations with the Israelites before he dies. Moses directs the Israelites to give the first fruits of their crops as an offering of thanks for their land and the bounty it produced. In the process, they are to remember the years of struggle and oppression suffered by the Israelites in Egypt and to acknowledge that G-D delivered the Israelites to a land flowing with milk and honey. It is an acknowledgment that what we produce should be credited both to our own hard work and to outside forces. Moses asks the Israelites to reflect on the fact that things had not always been easy, and that they had to endure some very hard times before making it to the promised land. In doing so, Moses implies that the rewards of our efforts may be even sweeter in light of the challenges that came before our successes.

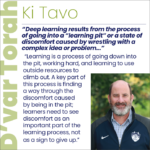

Educational theorist James Nottingham studies the role that challenge plays in the learning process. He explains that deep learning results from the process of going into a “learning pit” or a state of discomfort caused by wrestling with a complex idea or problem. Learning is a process of going down into the pit, working hard, and learning to use outside resources to climb out. A key part of this process is finding a way through the discomfort caused by being in the pit; learners need to see discomfort as an important part of the learning process, not as a sign to give up.

Quoted in the New York Times this summer, Nottingham describes three states of mind in which learners can find themselves: relative comfort, relative discomfort, and panic. When learners experience relative comfort, they may not be learning very much at all–the tasks are too easy. When learners panic, they also can’t learn. But when they experience relative discomfort, the best learning can happen. One of the key jobs for teachers and parents is to help our students distinguish between relative discomfort and panic, learn to see relative discomfort as a positive experience (because it means learning is happening), and persist in their learning process through that discomfort.

It is easy to see how this framework applies to something like learning how to ski. If you stay on the bunny slopes in relative comfort, you will never really master the sport. If you try to learn by starting on the most extreme terrain, your panic will take over and you will quit. But if you keep changing where you ski on the mountain to keep yourself in a state of relative discomfort, you will steadily improve your skiing. You may lose control at times and even fall down, but we all know and accept that that kind of failure is a part of the process of learning to ski.

Interestingly, students (and sometimes their parents) have a much harder time tolerating that kind of “falling”in the classroom. It can feel demotivating for students and can be brutal for parents to watch. However, if we want to produce graduates who have mastered the most important 21st-century skill, learning how to learn, we all need to help students see classroom discomfort and small failures as learning opportunities and a normal part of the learning process.

JCHS has put in place a lot of structures to normalize this kind of learning experience. For example, we report grades every six weeks but only put the final grade of the year on student transcripts, giving students as much learning runway as possible; all teachers offer some form of retests or rewrites on summative assessments; teachers increasingly do not include homework and FTWs as a part of student’s grades and use them only for feedback; teachers do not reduce students’ grades for turning in assignments late to allow students the time they need to show what they have learned. When learners make mistakes, parents and teachers need to be there for them with encouraging words, helping hands, and second chances.

As Dr. Rosen recently taught me, embracing and being comfortable with struggle is a part of the Jewish tradition. The name Israel comes from the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel. Before allowing the angel to leave, Jacob asks for a blessing. The angel replies: “Your name shall no longer be Jacob, for you have wrestled/struggled with beings divine & human and prevailed.” (Genesis 32:29) This highlights that to be a Jew—to be part of Israel—is to embrace struggle as a place that leads to blessing and growth.

Just as Moses in Ki Tavo asks the Jews to remember the hard times that preceded their harvest, it is our job to help our students learn to embrace the struggles that are a part of their learning.